News

Welcome to the Willowcroft blog! This is where we will be highlighting events and news from around the winery.

The Perfect Pour for Every Season

Wine isn’t just about what’s in the bottle—it’s about when and how you drink it. The same Cabernet Sauvignon that feels comforting by a winter fire might taste heavy and overpowering in the heat of August. Understanding how acidity, alcohol, and tannin interact with temperature can help you choose wines that not only fit the season but also enhance your mood and meals.

Acidity

Acidity gives wine its brightness and lift. In warm weather, high-acid wines like Virginia Albariño, Seyval, or Riesling feel crisp and refreshing. But serve them too cold, and those lively aromas can disappear, leaving the wine tasting overly sharp. Conversely, cooler weather naturally softens acidity, which is why that same Albariño can feel rounder and fuller in the fall.

Alcohol

Alcohol contributes to body and warmth. If a wine is served too warm—especially in summer—alcohol aromas can dominate and mask other flavors. A Virginia Petit Verdot or Cabernet Franc is far more enjoyable at its ideal serving temperature than when it’s been sitting out in the sun at a picnic.

Tannins

Tannins are the compounds that give certain red wines their structure and drying sensation. In full-bodied reds like Virginia Cabernet Sauvignon or Petit Verdot, tannins can become more pronounced and even harsh if served too warm. Cooler serving temperatures, especially in winter, can make them feel smoother and more integrated.

Warm Weather

Opt for wines with higher acidity and lighter bodies.

- Virginia Whites: Albariño, Seyval Blanc, Vidal Blanc, Traminette

- Light Reds: Chambourcin or even a gently chilled Cabernet Franc

- Rosé: Dry, crisp Virginia rosés that capture fresh berry flavors

- Sparkling Wines: Virginia Sauvage Rosé or Brut-style sparklers

These wines offer citrusy, floral, and bright fruit notes that refresh and energize on hot days.

Cool Weather

Choose wines with fuller bodies and richer textures for a warming effect.

- Virginia Reds: Petit Verdot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot

- White Rhône-style Varietals: Viognier, known in Virginia for its lush stone fruit and spice

These wines bring deeper fruit flavors, spice, and even earthy notes that feel right at home with cozy meals and sweaters.

- Spring: Bright, green flavors call for crisp wines. Virginia Sauvignon Blanc or Albariño is perfect with asparagus or herbed chicken, while a lighter Pinot Noir–style Chambourcin pairs beautifully with roasted spring vegetables.

- Summer: Chilled Riesling or rosé alongside grilled seafood, salads, or watermelon-feta skewers is a warm-weather dream.

- Fall: As flavors turn richer, medium-bodied wines like Virginia Merlot or oaked Chardonnay complement roasted squash, mushrooms, and pork tenderloin.

- Winter: Bold reds like Petit Verdot, Cabernet Sauvignon, or a Bordeaux-style blend stand up to beef stews, braised short ribs, or a spread of local cheeses.

- Happy or Relaxed: Lighter, zippy wines—think Albariño, Riesling, or sparkling—can amplify a sunny mood.

- Contemplative or Cozy: Fuller reds with velvety textures, such as Merlot or Petit Verdot, invite you to slow down and savor.

- Sparkling & Crisp Whites: 40–50°F

- Fuller Whites & Rosé: 50–55°F

- Light Reds: 55–60°F (yes, this means chilling them slightly in summer)

- Full-bodied Reds: 60–65°F

By matching wine style to the season and respecting its ideal serving temperature, you not only taste the wine at its best—you experience it as the winemaker intended.

Why Bottle Age Changes Wine — and When to Drink or Hold

A great bottle of wine is not frozen in time. From the day it’s sealed, it begins a quiet transformation — a slow, graceful evolution that can soften sharp edges, deepen flavors, and reveal hidden layers. But not every wine benefits from long cellaring, and knowing when to drink or hold is part science, part art, and part joyful gamble.

Inside every bottle, a subtle dance is taking place. As wine ages, tannins — the natural compounds responsible for a wine’s astringency — slowly polymerize, forming longer molecular chains. This process softens the tannic bite, creating the velvety, supple mouthfeel that defines beautifully aged reds.

Other chemical changes happen as well:

- Color shifts — Reds often deepen, then gradually turn brick or garnet at the rim. Whites may take on richer gold or amber tones.

- Fruit flavors evolve — Primary, fresh-fruit notes give way to more complex, savory, or dried-fruit characters.

- Astringency mellows — Harsh or “green” flavors smooth out.

- Mouthfeel softens — Tannins integrate, and some whites gain a waxy or oily texture.

A well-stored bottle is an active aging vessel, its contents changing in both chemistry and character.

Young wines are dominated by primary aromas — fresh fruit, flowers, and herbs. Over time, some of these fade as the compounds responsible (like geraniol for rose or isoamyl acetate for banana) break down. But new characters emerge, thanks to gentle oxygen exposure through the cork.

These tertiary aromas can include:

- Walnut, caramel — linked to the compound sotolon

- Almond — from benzaldehyde

- Honey — from phenylacetaldehyde

The result is a wine that shifts from bright and fruity to layered, savory, and contemplative.

Even among wines built to age, there’s a sweet spot:

- Too young — flavors are primary, tannins may be rough

- Just right — a balance of fruit, structure, and complexity

- Too old — aromas fade, structure collapses, and freshness is lost

Exactly where a wine’s peak falls depends on the grape, winemaking style, storage conditions, and personal taste.

- Grand Cru Classé Bordeaux

- Barolo (Nebbiolo)

- Vintage Champagne

- Madeira, Sherry, Port

- Tokaji Aszú

- Vin Jaune from Jura

- Provence Rosé

- Moscato d’Asti

- Light Sauvignon Blanc

- Most canned or boxed wines

- High flavor intensity — Bold aromatics that can evolve

- Natural preservative qualities — High acidity, firm tannin, or fortification with alcohol

- A 20-year-old wine can be glorious — but only if the style, vintage, and storage align.

To give your bottles their best chance at graceful aging:

- Keep them at a cool, constant temperature (ideally 55°F / 13°C)

- Store them away from light and vibration

- Lay bottles on their side to keep corks moist

- If your home conditions aren’t ideal, consider professional wine storage.

For many wine lovers, part of the joy in aging a bottle isn’t just about the chemistry — it’s about the story it carries. Over the years, a wine evolves quietly, much like our own lives, growing softer, deeper, and more layered with character.

Opening a well-aged bottle can feel like unlocking a memory. The first swirl brings back the moment you bought it — a visit to a favorite vineyard, a shared celebration, or a trip that left its mark. The aromas and flavors are richer, but so too is the meaning.

Aged wine invites us to slow down, to savor not just what’s in the glass, but the journey that brought it there. And sometimes, that journey is as satisfying as the wine itself.

Some wines — rare Bordeaux vintages, certain Burgundies, collectible Napa Cabernets — may appreciate in value over time. But the market is unpredictable, and storage costs can erode profits. For most of us, the richest return on aging wine is the joy of sharing it.

The surest way to know if a wine has peaked? Open it. Taste it. Enjoy it. Wine is meant to be shared, not just stored. And while patience can reward you with a transcendent sip, a bottle opened with friends is never “too soon.”

Barrel Talk: How Oak Shapes the Soul of Wine

At Willowcroft, every barrel in our cellar has a story to tell—about the forest it came from, the fire that toasted it, and the wines that called it home. Oak barrels aren’t just vessels; they’re power tools that shape a wine’s texture, aroma, and flavor in ways that are both subtle and profound.

Let’s start with the basics: why use oak at all?

Oak allows minute amounts of oxygen to seep into the wine over time—a slow exchange that helps soften tannins, stabilize color, and encourage complexity. But that’s just the beginning. The wood itself contains compounds like lignin, lactones, and tannins that interact with wine to create distinctive flavor notes—think vanilla, spice, coconut, and clove.

Different oak species contribute different flavors and structures:

- French Oak (Quercus petraea): Known for its tight grain and slow extraction, French oak imparts elegant spice notes—cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg—along with a silky mouthfeel. It’s subtle and refined, often used for age-worthy reds and delicate whites.

- American Oak (Quercus alba): With a looser grain, American oak offers a more aggressive flavor profile—coconut, dill, and sweet baking spices like vanilla and nutmeg come forward more quickly. It’s a favorite for bold reds and rich whites that can stand up to its signature punch.

- Hungarian Oak (Quercus robur): Grown in the Zemplén Mountains, Hungarian oak splits the difference between French and American. It brings soft spice and creamy texture, with less sweetness than American oak and more expressiveness than French. A rising favorite for structured whites and balanced reds.

Coopers (barrel-makers) apply fire to the inside of the barrel—a process called toasting. This heat treatment breaks down oak compounds, creating new flavors.

- Light Toast: Preserves more of the wood’s raw tannins and structure. Ideal for whites, as it adds subtle spice without overwhelming freshness.

- Medium Toast: The most versatile—offering a balance of vanilla, caramel, and soft clove. It is often used for reds like Merlot or Cabernet Franc.

- Heavy Toast: Think smoke, roasted coffee, dark chocolate—great for big reds like Petit Verdot or Chambourcin that can handle the depth.

Not all barrels make the same impression—especially as they age.

- New Oak: Delivers the most substantial impact, with the most flavor extraction. Wines aged in new barrels will show clear notes of toast, spice, and structure.

- Used Oak: A second or third vintage in the barrel gives a more restrained oak influence. Used barrels still allow for micro-oxygenation, but the flavor contribution is gentler.

- Neutral Oak: After several uses, barrels no longer impart much flavor but continue to support the wine’s development through slow oxygen contact. They're a subtle tool, often used to preserve the natural fruit and terroir expression.

Oak barrels aren’t just storage—they’re storytellers. Each barrel influences a wine’s aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel, often in ways that define the wine’s identity. A typical 60-gallon barrel costs $900–$1,500, depending on the oak’s origin and toast level.

At Willowcroft, we thoughtfully blend new, used, and neutral barrels to craft balanced wines that highlight both the vineyard and the wood. Curious to taste the difference? Join us in the tasting room and ask which of our wines saw oak—you might be surprised how much that barrel adds to your glass.

Want more vineyard secrets? Explore our blog series and discover how elements like dry farming, yeast, and rootstock quietly shape every bottle.

Fermentation by Design: How Yeast Creates Style, Texture, and Taste

In our previous blog (Native Yeast vs. Cultured Yeast, posted August 5), we explored how winemakers choose between wild and commercial yeast to begin fermentation. But once that decision is made, the real work begins. Yeast doesn’t just start fermentation—it has an ongoing and powerful influence on how a wine tastes, feels, and evolves.

In Part 2 of our yeast series, we examine what happens after yeast is introduced and how its role influences the final product. From citrusy aromatics to creamy textures and decisions about sweetness, yeast is one of the most essential style tools in a winemaker’s hands.

The primary role of yeast is to convert the sugars in grape juice into alcohol and carbon dioxide. But along the way, yeast produces hundreds of aromatic and textural compounds. These include esters, alcohols, and amino acids that contribute to the wine’s overall flavor and mouthfeel.

The aromas we associate with different styles of wine—like citrus in a white or stone fruit in a rosé—can often be linked to the specific yeast strain used and the fermentation conditions selected. Many of these flavor notes are not found in the grapes themselves but are byproducts of fermentation.

Cultured yeasts are developed to offer specific benefits, such as promoting clean fermentation, enhancing certain aromas, or improving texture. Winemakers can select strains that support their vision for the wine, whether that’s preserving crisp acidity, deepening the mouthfeel, or ensuring a slow, even fermentation.

At Willowcroft, we thoughtfully select yeast strains based on the varietal, the vintage, and the desired outcome. Using cultured yeast enables us to consistently support clean, healthy fermentations and accurately express the style of each wine. For example, we may select strains that enhance floral or citrus notes in white wines or those that develop more structure and a smooth texture in reds. Our choices are strategic and driven by experience, with an emphasis on preserving balance, character, and purity in the final product.

Temperature is a key factor in how yeast behaves. Cooler fermentations tend to slow yeast activity and preserve more delicate aromatics, especially in white and rosé wines. This is how you get those fresh citrus or melon notes. Warmer fermentations, more typical for reds, encourage greater extraction of tannin and color and can emphasize deeper, more robust flavors.

By controlling fermentation temperature in conjunction with yeast selection, winemakers can shape the overall tone of the wine—from bright and fruit-forward to rich and layered.

Sometimes, fermentation is intentionally stopped before the yeast has converted all of the sugar into alcohol. This results in a wine with residual sugar and a naturally off-dry or semi-sweet profile. In cool-climate wines with high acidity, that small amount of sugar can create balance and lift. In others, it helps highlight specific fruit characteristics.

Stopping fermentation requires precision. The wine may be chilled to slow yeast activity, filtered to remove yeast cells, or treated with sulfur to inhibit further fermentation. These decisions must be made carefully and are often best executed when using cultured yeast, which offers predictability and cleaner outcomes.

At Willowcroft, this approach is used selectively to craft wines that remain vibrant and well-balanced, especially in varietals like Vidal Blanc or Traminette, where a touch of natural sweetness can elevate aromatics and round out the palate.

After fermentation, yeast cells settle in the wine and form what’s called the lees. In some wines, particularly white wines and sparkling wines, aging the wine on its lees can enhance richness and complexity. As the yeast cells break down, they release compounds that contribute a creamy or silky texture and subtle notes, such as those of fresh bread or nuttiness. This process—called autolysis—is a hallmark of traditional-method sparkling wine, but also plays a role in shaping the mouthfeel of certain still wines.

Lees contact is another example of how yeast contributes to the wine long after fermentation is complete, adding both weight and finesse to the wine.

Yeast is often referred to as the "invisible ingredient" in wine, but its impact is anything but subtle. Through careful strain selection, temperature control, and fermentation management, winemakers guide the development of aroma, structure, and balance.

At Willowcroft, our approach to yeast is thoughtful and deliberate. Every choice is made to support the fruit, the vintage, and the expression of the vineyard itself. Whether we’re working with a bright Albariño or a structured Petit Verdot, our yeast decisions help carry each wine from grape to glass with clarity and integrity.

Fermentation is far more than a chemical reaction—it’s a design process. Yeast doesn’t just make wine; it shapes it. From flavor to finish, yeast is one of the most potent tools in winemaking, allowing the character of the vineyard to take form in the bottle.

When you enjoy a glass of Willowcroft wine, you’re tasting more than fruit. You’re tasting the result of carefully considered choices made during fermentation—choices that preserve freshness, amplify expression, and deliver a wine with style and purpose.

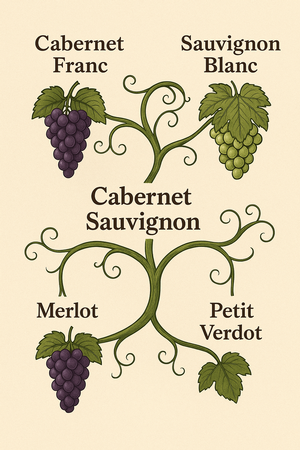

Wine Families: Why Certain Grapes Share Similar Traits

If you’ve ever wondered why Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot often feel like siblings in a Bordeaux blend—or why Sauvignon Blanc seems to “get” Cabernet Sauvignon so well—there’s a good reason for that. Like people, grape varieties have lineages, and once you trace their “family trees,” the patterns in flavor, structure, and style start to make a lot more sense.

Let’s explore some of the most fascinating grape family connections and how they show up in your glass.

Cabernet Sauvignon is one of the world’s most celebrated red grapes, and it's actually the result of a spontaneous crossing between Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. Yes, a red and a white grape got together in 17th-century France and created something bold, structured, and deeply age-worthy.

This lineage explains Cabernet Sauvignon’s herbaceous edge and high acidity (from Sauvignon Blanc), as well as its structure and red-fruited depth (from Cabernet Franc). At Willowcroft, we celebrate this legacy with our own elegant, hillside-grown Cabernet Sauvignon.

As one of the parent grapes of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc tends to be lighter and more floral, with notes of red cherry, violets, and gentle spice. It’s often used as a blending grape but is captivating on its own—especially when grown in Virginia, where it shows bright acidity and savory character.

At Willowcroft, our Cabernet Franc is a perennial favorite. With a soft spice profile and polished tannins, it captures both the old-world charm and new-world vibrancy of the grape.

While not a direct descendant, Merlot is considered a close relative in the Bordeaux family. It shares Cabernet Sauvignon’s red and black fruit notes but leans softer and more plush. Think velvet instead of leather.

In blends, Merlot offers a roundness that complements Cabernet Sauvignon’s power—proof that sometimes the best family traits come out when siblings collaborate.

Another Bordeaux native, Petit Verdot, is often the last to ripen and the first to impress. It brings dark color, robust tannins, and brooding black fruit to the table. Though it’s used sparingly in blends, its impact is undeniable.

Here at Willowcroft, we bottle Petit Verdot as a varietal wine to let its dark intensity shine—proof that even the wild cousins have their place at the table.

You might not expect a crisp white wine like Sauvignon Blanc to be related to one of the most robust reds, but genetics tells the story. As one of Cabernet Sauvignon’s parents, Sauvignon Blanc contributes aromatic lift and high acidity.

You can still see that DNA shine through when enjoying a glass of Willowcroft Cabernet Sauvignon—especially in its structure and finesse.

Understanding grape family trees isn’t just trivia—it can change how you taste. If you love the smoky elegance of Cabernet Franc, you might find yourself drawn to a structured Cabernet Sauvignon. Enjoying the citrus pop of Sauvignon Blanc? That zing might feel familiar when you taste a young Cab.

At Willowcroft, we honor these lineages by crafting wines that let their heritage speak. Dry-farmed on the Catoctin Ridge and nurtured by nature, each of our grapes tells a generational story—one rooted in history and expressed in every bottle.

Next time you visit us, ask for a flight that highlights our Bordeaux-family reds. You’ll taste the genetics at work—and maybe discover a new favorite among the wine world’s most fascinating family tree.

Native Yeast vs. Cultured Yeast: Who’s Fermenting Your Wine?

When you think of what gives wine its flavor, you might picture grapes, barrels, or even the soil beneath the vines. But one of the most powerful forces shaping your wine’s personality is microscopic: yeast.

Yeast is what turns grape juice into wine. Without it, there’s no fermentation—no alcohol, no aroma development, and no complexity. But not all yeast is the same. Winemakers must choose between using native (wild) yeast or cultured (commercial) strains, and that decision can have a significant impact on the final product.

At Willowcroft, we carefully select yeast for each wine, balancing the expression of place with fermentation stability. So what’s the difference between native and cultured yeast—and why does it matter?

Yeast’s job in winemaking is to consume the sugars in grape juice and convert them into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and hundreds of aromatic compounds that contribute to flavor, texture, and aroma.

The superstar of the fermentation world is a species called Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It’s found all over vineyards, cellars, and winery equipment—and is the dominant player in both native and cultured fermentations.

But how that yeast gets into the fermentation tank is where things diverge.

Native yeast refers to the wild strains naturally present on grape skins, in the vineyard environment, and in the winery itself. When a winemaker allows fermentation to occur spontaneously, without adding commercial yeast, these ambient strains kick off the process.

Benefits of native yeast:

- Terroir expression: Native yeasts are unique to each vineyard and vintage, potentially offering more distinctiveness and complexity.

- Minimal intervention: Wild fermentation aligns with low-intervention, sustainable winemaking philosophies.

- Flavor nuance: A variety of yeast strains can contribute layers of aroma and mouthfeel, especially early in fermentation.

Risks of native yeast:

- Unpredictability: Some wild strains may start fermentation but struggle to finish it.

- Higher chance of spoilage: If undesirable microbes take over, it can lead to off-flavors or stuck fermentations.

- Longer fermentation time: Native ferments are typically slower and require more monitoring.

In cooler climates or low-sugar grape musts, native fermentation can be an elegant choice. But in warmer, more humid regions like Virginia, where microbial pressure is higher, the risks must be carefully managed.

Cultured yeasts are laboratory-selected strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae developed for consistency, efficiency, and targeted winemaking outcomes. They’re available in a wide array of strains—each suited to different grape varieties, fermentation temperatures, and desired wine styles.

Commonly used strains include:

- EC-1118: Excellent for sparkling wine and high-alcohol fermentations

- D47: Often used in whites like Chardonnay for fuller mouthfeel and citrus notes

- RC212: A go-to for Pinot Noir and other delicate reds to enhance berry flavors

Benefits of cultured yeast:

- Predictable results: Reliable fermentation from start to finish

- Tailored performance: Choose a strain to match the wine’s style, structure, and flavor goals

- Lower risk of spoilage: Outcompetes unwanted wild microbes

Limitations:

- Less spontaneity: You sacrifice some of the unknown character and potential complexity of a native ferment

- Less expression of place: Commercial yeast may dominate the flavor profile instead of the vineyard

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Some winemakers swear by native fermentation for its authenticity. Others rely on cultured yeast for precision and peace of mind.

At Willowcroft, we recognize the value of both approaches. For certain small-batch or expressive wines, native fermentations can shine. For other wines—particularly those with delicate balance or specific style goals—cultured strains offer important control and consistency.

Ultimately, the best yeast is the one that lets the grape, the vintage, and the vineyard speak most clearly.

Yeast may be invisible, but its impact is undeniable. Whether wild or cultured, the tiny organisms doing the heavy lifting during fermentation help craft every swirl, sniff, and sip.

So next time you enjoy a Willowcroft wine, know that behind the scenes—at a cellular level—a carefully chosen yeast helped shape that wine’s unique story.

Wine Diamonds: Not a Flaw, But a Sign of Quality

What Those Crystals in Your Wine Bottle Really Mean

Ever poured a beautiful glass of wine and noticed a few shimmering crystals at the bottom, or maybe clinging to the cork? If your first instinct was concern, you’re not alone.

But don’t worry—those sparkly specks are known as tartrate crystals, or more affectionately: wine diamonds. They’re not only harmless, they’re a sign that your wine is authentic, natural, and minimally processed.

At Willowcroft, where we emphasize gentle winemaking and purity of expression, wine diamonds are simply part of the story. Let’s explore what they are, why they form, and why they’re worth celebrating, not avoiding.

Tartrate crystals are solid deposits that form when tartaric acid, one of the key natural acids in grapes, binds with potassium, another naturally occurring element in wine. These two components can join to form potassium bitartrate—the same compound you may know as cream of tartar in your baking cabinet.

Over time, especially in cooler temperatures, these crystals can settle at the bottom of the bottle or adhere to the cork.

Tartaric acid is temperature-sensitive. When wine—especially white wine—is chilled to very low temperatures (typically below 40°F / 4°C), it becomes less able to hold tartaric acid in solution. As a result, the acid precipitates out as crystals.

You’re more likely to see wine diamonds if:

- The wine has been stored in the fridge for an extended period

- The wine has not undergone cold stabilization, a common (but optional) winemaking step

- The wine is high in natural acidity, like many of the crisp, aromatic whites Willowcroft produces

Wine diamonds don’t affect the flavor, aroma, texture, or safety of the wine in any way. In fact, their presence can actually signal quality and integrity.

They’re natural – They’re made of grape components, not foreign substances.

They mean the wine is minimally processed – Wines that skip cold stabilization (a process where wine is chilled to force these crystals out before bottling) retain more of their natural acidity, freshness, and age-worthiness.

They signal gentle handling – The absence of over-filtration or additives shows that the winemaker chose to let the wine speak for itself.

First, smile—you’ve got the good stuff. But if the appearance of wine diamonds bothers you, here’s what you can do:

- On the cork? Just wipe them off with a napkin or cloth.

- In the bottle? Either:

- Decant the wine through a mesh strainer, cheesecloth, or coffee filter

- Let the crystals settle at the bottom and pour gently to avoid disturbing them

They’re completely safe to consume, but most people prefer to leave them in the bottle.

We believe that the best wines come from thoughtful farming and restrained winemaking. That means embracing the occasional natural element—like wine diamonds—as part of a wine’s story.

When you choose a Willowcroft white wine that hasn’t been cold stabilized, you’re tasting more than just fruit—you’re tasting the vineyard, the vintage, and the winemaker’s respect for nature.

Wine diamonds may look unusual, but they’re a sparkling sign of authenticity. In an industry filled with manipulation, they stand as a reminder that great wine isn’t always perfectly polished—it’s honest.

So the next time you find crystals in your bottle, don’t fret. Consider it a gem of a discovery.

Old Vines, Timeless Wines: What 40+ Years Means in the Vineyard

A Willowcroft Perspective on the Power of Age

A Willowcroft Perspective on the Power of Age

In wine, there’s something magical about the word “old.” Old cellars, old barrels, old vintages—and, of course, old vines. But what does “old vine” actually mean? Is there a specific age? A special certification? Or is it simply marketing?

At Willowcroft, many of our original vines—planted in 1981—are now over 40 years old, making them among the oldest in Virginia. These vines, with decades of seasons behind them, produce fruit that reflects both history and resilience.

Let’s explore what makes an old vine special—and how their quiet strength shows up in your glass.

Surprisingly, there’s no universal legal definition for "old vine." In most wine regions, it’s a subjective term. That said, here’s a general guide:

Vines 20-30 years old often start to qualify as "old" in terms of reduced yields and increased concentration.

Many producers and organizations see 50+ years as the gold standard for truly old vines.

At Willowcroft, our 40+ year-old vines sit comfortably in that distinguished middle, with maturity that shines through vintage after vintage.

As vines age, their growth slows. They produce smaller yields, but the fruit tends to have a greater concentration of flavor and aroma. These berries often pack more intense sugars, acids, and phenolic compounds, translating into wines with depth and complexity.

- 💧 Deep Roots:

Older vines develop extensive root systems, reaching deep into the soil to access water and nutrients younger vines can’t. This not only helps in dry conditions but also allows the grapes to draw from a broader palette of minerals, adding layers of terroir expression to the wine. - 🌞 Resilience:

With decades of adaptation, old vines can better handle environmental stresses—whether it’s a hot, humid Virginia summer or an unusually dry season. Their established systems make them naturally hardy. - 🪞 Terroir on Display:

Because they rely less on surface water and nutrients, old vines are more influenced by the deeper subsoil. This means their fruit often captures the true character of the vineyard’s terroir—soil, slope, and climate in harmonious balance.

While every vineyard and varietal is different, old vine wines are often described as:

- More concentrated in fruit flavor

- Silky in texture with fine, integrated tannins

- Complex, offering layered aromas and a longer finish

- Balanced, thanks to consistent, even ripening

At Willowcroft, you may notice these qualities in wines like our Chardonnay or Cabernet Franc, crafted from vines that have been growing since Ronald Reagan was president and MTV still played music videos.

When we planted our first vines in 1981, we couldn’t have known how their deep roots would shape not only our wines but also the history of Virginia winemaking. These vines, now over four decades old, are living proof that patience in the vineyard pays off in the glass.

Each harvest is a reflection of their long relationship with the land, through droughts, storms, and sunny seasons alike.

So next time you see “old vine” on a bottle—or sip a Willowcroft wine made from 40+ year-old fruit—pause for a moment. You’re tasting not just grapes but the echoes of years past: the summers, the storms, and the steady work of roots digging deep into Catoctin Ridge.

Visit us and experience wines crafted from some of Loudoun’s oldest vines. Every pour is a piece of Willowcroft’s 40+ year legacy.

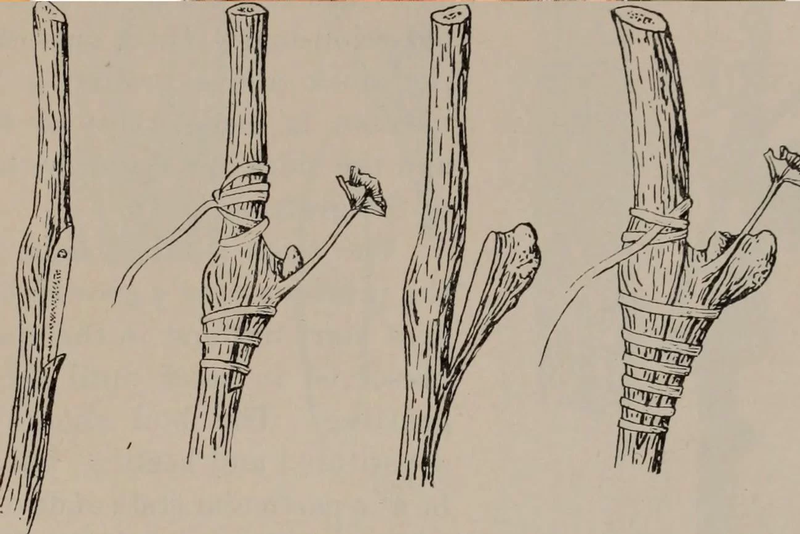

Rootstock Rebellion: How the Bottom Half of the Vine Shapes the Wine

The Unsung Hero Beneath Every Great Vintage

Ask a wine lover to name what shapes a wine’s character, and you’ll hear about grape varieties, climate, barrels—even yeast. But there’s one key player almost no one talks about: rootstocks.

These humble underground structures don’t make headlines or tasting notes, but they’re the very foundation of modern viticulture. They protect against pests, adapt vines to challenging soils, and influence everything from how grapes ripen to how the wine tastes. At Willowcroft, where we farm without irrigation and face Virginia’s humid summers, choosing the right rootstock isn’t optional—it’s vital.

So why don’t we hear more about them? To answer that, let’s dig into history, science, and a little Texas-sized adventure.

In simplest terms, a rootstock is the underground part of the vine—the roots—that’s grafted to the fruiting vine (the part above ground that produces the grapes). The fruiting vine is typically Vitis vinifera, the classic European grapevine species behind beloved varietals like Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot.

The rootstock, however, often comes from other grape species. Why? Because it acts like the engine of growth, protecting vines from pests, diseases, and environmental stress. It also influences vigor, water uptake, nutrient absorption, and even how a grapevine copes with Virginia’s frequent heat and humidity.

Rootstocks became essential during the 19th century when Europe’s vineyards were nearly wiped out by phylloxera, a tiny root-feeding insect native to North America. European vinifera vines had no resistance to the pest. The solution? Grafting them onto American rootstocks, which had evolved alongside phylloxera and developed natural defenses.

The first rootstocks tried—Vitis riparia—thrived in moist, fertile riverbank soils but failed in the dry, calcareous soils of regions like Champagne and Burgundy. Then came Vitis rupestris, better suited to stony soils but still unhappy in limestone-rich areas.

The breakthrough came when botanists like Pierre Viala and Thomas Volney Munson identified Vitis Berlandieri, a Texas native thriving in dry, chalky soils. Though difficult to propagate, Berlandieri became the backbone for hybrid rootstocks like 41B, which saved French vineyards and remains in use today.

Virginia’s climate brings its own set of hurdles for grapevines. Our summers often deliver long stretches of heat and humidity without relief, creating the perfect conditions for fungal diseases like powdery mildew and botrytis. Pair that with dry-farmed hillsides and variable soils, and rootstock selection becomes not just important, but essential.

The right rootstock helps balance vigor, resist disease, and manage water uptake in these demanding conditions. Some, like Petit Verdot’s small, tight clusters, naturally help resist moisture intrusion, but beneath the surface, it’s the rootstock doing much of the heavy lifting.

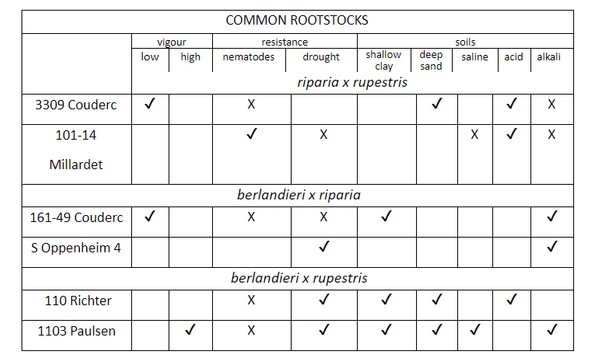

💡 To better understand how different rootstocks perform, here’s a quick chart showing key rootstock types, their strengths, and where they shine in the vineyard:

This snapshot helps demystify the role of rootstocks and shows why their selection matters as much as the grape variety grafted above them.

Today, nearly all commercial vineyards rely on rootstocks derived from the same small group of species: vinifera, riparia, rupestris, and Berlandieri. But nature doesn’t stand still. Phylloxera has evolved into numerous biotypes and superclones, while climate change introduces new challenges like extreme drought and shifting soil salinity.

Some researchers are exploring wild Asian grape species for new traits. Others argue for modern methods, including genetic modification (GM), to develop next-generation rootstocks. This remains controversial, but so was grafting American roots to French vines—until it saved the world’s wine industry.

Rootstocks are more than a technicality—they shape:

🌿 Vine vigor and health

💧 Drought tolerance and disease resistance

🍇 Ripening speed and fruit quality

🌱 Sustainability in challenging climates

At Willowcroft, we see them as quiet partners in the vineyard, helping us produce elegant, expressive wines—year after year—even in Virginia’s demanding environment.

So next time you swirl a glass of Petit Verdot or Chardonnay, raise a silent toast to the roots beneath your feet.

Visit Willowcroft for a tasting or tour, and ask us about the vines in your glass. There’s a world of science and history lying just below the soil.

🍇 Grape Clones & Hybrids: What They Are and Why They Matter

A Willowcroft Deep Dive into the Genetics of Great Wine

Not all Chardonnay is created equal.

Not even all Merlot.

In fact, even within the same vineyard block, the grapes growing just a few feet apart might come from entirely different genetic lineages.

Most wine lovers are surprised to learn how much grape genetics influence what’s in their glass. At Willowcroft, we take pride in our deep connection to both classic vinifera grapes—like Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay, which were among our original plantings—and to modern hybrid varieties that have helped us thrive in Virginia’s unique growing environment.

Understanding how clones and hybrids work is key to appreciating the science and artistry behind every bottle we produce. And no, none of this involves GMOs—so let’s set the record straight.

Clones are genetically identical copies of a single "mother vine" that showed exceptional traits, like superior flavor, disease resistance, or early ripening. Cuttings, not seeds, propagate these vines, allowing them to retain the exact DNA of their origin.

Think of clones as siblings from the same exceptional parent, each expressing slightly different characteristics based on where they’re planted. For example, Chardonnay Clone 96 may bring out bright citrus and body, while Clone 76 delivers more floral and elegant tones.

Across the industry, clonal selection is key to maximizing quality. It helps us:

- Adapt to different vineyard blocks

- Improve disease resistance naturally

- Fine-tune flavor and ripening windows for our dry-farmed, hillside sites

From the beginning, Willowcroft has championed vinifera—the noble European species behind the world’s most iconic wines. Our early plantings of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay were rooted in this tradition and remain foundational to our portfolio today.

But Virginia is not Bordeaux or Burgundy. Our summers bring persistent heat and humidity, often without a reprieve from the heat. These humid streaks—lasting days, weeks, or even months—can place significant stress on the vines, increasing the risk of fungal diseases, rot, and uneven ripening. That’s where clonal selection and strategic hybrid use become critical. By selecting varietals and clones adapted to our specific conditions—such as Petit Verdot, whose small, tight clusters naturally help resist moisture intrusion—we can produce wines of integrity, character, and resilience, even in challenging years.

Hybrid grapes are crosses between different grape species, typically blending vinifera with native American grapes like Vitis labrusca or Vitis riparia. These intentional crosses are bred for strength: they’re often more resistant to disease, cold, humidity, and pests.

At Willowcroft, we proudly grow several hybrids that have earned fan-favorite status:

- Seyval Blanc – Crisp and citrusy, great for warm days and cool nights

- Chambourcin – Deep, fruit-forward, and perfect with pork or lamb

- Traminette – Spicy and floral, with Gewürztraminer in its lineage

Here’s the truth:

Hybrids are not genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Hybrids are created through traditional plant breeding—crossing two grape varieties and selecting the best offspring. It’s a slow, deliberate process, often taking years or even decades.

GMOs, on the other hand, involve lab-based DNA manipulation, often introducing genes from unrelated species. Currently, no GMO grapes are used in commercial winemaking in the United States.

So while some folks hear “hybrid” and think “science experiment,” the reality is that hybrids are a time-honored, nature-guided solution to challenges like climate, pests, and sustainability.

Your wine starts long before the bottle—with decisions about what to plant, where, and why. Whether we’re choosing a Cab Franc clone for improved ripening or a hybrid like Seyval to reduce disease pressure, every choice in the vineyard shapes what you taste in the glass.

These selections affect:

- 🍇 Flavor profiles and aromatic intensity

- 🌿 Farming sustainability (especially in dry-farmed systems like ours)

- 🌦️ Adaptation to climate and disease pressure

- 📦 Consistency across vintages and vineyard blocks

Join us in the tasting room or attend one of our vineyard tours to see how these choices play out in real time, from bud break to bottle. The more you know, the better it tastes—and we’re always happy to pour and chat.