News

Welcome to the Willowcroft blog! This is where we will be highlighting events and news from around the winery.

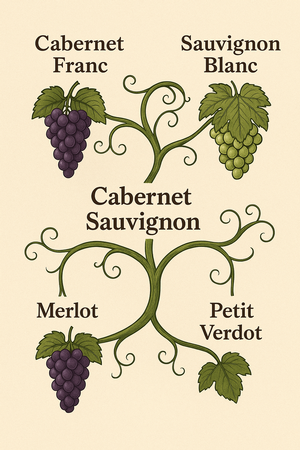

Wine Families: Why Certain Grapes Share Similar Traits

If you’ve ever wondered why Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot often feel like siblings in a Bordeaux blend—or why Sauvignon Blanc seems to “get” Cabernet Sauvignon so well—there’s a good reason for that. Like people, grape varieties have lineages, and once you trace their “family trees,” the patterns in flavor, structure, and style start to make a lot more sense.

Let’s explore some of the most fascinating grape family connections and how they show up in your glass.

Cabernet Sauvignon is one of the world’s most celebrated red grapes, and it's actually the result of a spontaneous crossing between Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. Yes, a red and a white grape got together in 17th-century France and created something bold, structured, and deeply age-worthy.

This lineage explains Cabernet Sauvignon’s herbaceous edge and high acidity (from Sauvignon Blanc), as well as its structure and red-fruited depth (from Cabernet Franc). At Willowcroft, we celebrate this legacy with our own elegant, hillside-grown Cabernet Sauvignon.

As one of the parent grapes of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc tends to be lighter and more floral, with notes of red cherry, violets, and gentle spice. It’s often used as a blending grape but is captivating on its own—especially when grown in Virginia, where it shows bright acidity and savory character.

At Willowcroft, our Cabernet Franc is a perennial favorite. With a soft spice profile and polished tannins, it captures both the old-world charm and new-world vibrancy of the grape.

While not a direct descendant, Merlot is considered a close relative in the Bordeaux family. It shares Cabernet Sauvignon’s red and black fruit notes but leans softer and more plush. Think velvet instead of leather.

In blends, Merlot offers a roundness that complements Cabernet Sauvignon’s power—proof that sometimes the best family traits come out when siblings collaborate.

Another Bordeaux native, Petit Verdot, is often the last to ripen and the first to impress. It brings dark color, robust tannins, and brooding black fruit to the table. Though it’s used sparingly in blends, its impact is undeniable.

Here at Willowcroft, we bottle Petit Verdot as a varietal wine to let its dark intensity shine—proof that even the wild cousins have their place at the table.

You might not expect a crisp white wine like Sauvignon Blanc to be related to one of the most robust reds, but genetics tells the story. As one of Cabernet Sauvignon’s parents, Sauvignon Blanc contributes aromatic lift and high acidity.

You can still see that DNA shine through when enjoying a glass of Willowcroft Cabernet Sauvignon—especially in its structure and finesse.

Understanding grape family trees isn’t just trivia—it can change how you taste. If you love the smoky elegance of Cabernet Franc, you might find yourself drawn to a structured Cabernet Sauvignon. Enjoying the citrus pop of Sauvignon Blanc? That zing might feel familiar when you taste a young Cab.

At Willowcroft, we honor these lineages by crafting wines that let their heritage speak. Dry-farmed on the Catoctin Ridge and nurtured by nature, each of our grapes tells a generational story—one rooted in history and expressed in every bottle.

Next time you visit us, ask for a flight that highlights our Bordeaux-family reds. You’ll taste the genetics at work—and maybe discover a new favorite among the wine world’s most fascinating family tree.

Native Yeast vs. Cultured Yeast: Who’s Fermenting Your Wine?

When you think of what gives wine its flavor, you might picture grapes, barrels, or even the soil beneath the vines. But one of the most powerful forces shaping your wine’s personality is microscopic: yeast.

Yeast is what turns grape juice into wine. Without it, there’s no fermentation—no alcohol, no aroma development, and no complexity. But not all yeast is the same. Winemakers must choose between using native (wild) yeast or cultured (commercial) strains, and that decision can have a significant impact on the final product.

At Willowcroft, we carefully select yeast for each wine, balancing the expression of place with fermentation stability. So what’s the difference between native and cultured yeast—and why does it matter?

Yeast’s job in winemaking is to consume the sugars in grape juice and convert them into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and hundreds of aromatic compounds that contribute to flavor, texture, and aroma.

The superstar of the fermentation world is a species called Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It’s found all over vineyards, cellars, and winery equipment—and is the dominant player in both native and cultured fermentations.

But how that yeast gets into the fermentation tank is where things diverge.

Native yeast refers to the wild strains naturally present on grape skins, in the vineyard environment, and in the winery itself. When a winemaker allows fermentation to occur spontaneously, without adding commercial yeast, these ambient strains kick off the process.

Benefits of native yeast:

- Terroir expression: Native yeasts are unique to each vineyard and vintage, potentially offering more distinctiveness and complexity.

- Minimal intervention: Wild fermentation aligns with low-intervention, sustainable winemaking philosophies.

- Flavor nuance: A variety of yeast strains can contribute layers of aroma and mouthfeel, especially early in fermentation.

Risks of native yeast:

- Unpredictability: Some wild strains may start fermentation but struggle to finish it.

- Higher chance of spoilage: If undesirable microbes take over, it can lead to off-flavors or stuck fermentations.

- Longer fermentation time: Native ferments are typically slower and require more monitoring.

In cooler climates or low-sugar grape musts, native fermentation can be an elegant choice. But in warmer, more humid regions like Virginia, where microbial pressure is higher, the risks must be carefully managed.

Cultured yeasts are laboratory-selected strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae developed for consistency, efficiency, and targeted winemaking outcomes. They’re available in a wide array of strains—each suited to different grape varieties, fermentation temperatures, and desired wine styles.

Commonly used strains include:

- EC-1118: Excellent for sparkling wine and high-alcohol fermentations

- D47: Often used in whites like Chardonnay for fuller mouthfeel and citrus notes

- RC212: A go-to for Pinot Noir and other delicate reds to enhance berry flavors

Benefits of cultured yeast:

- Predictable results: Reliable fermentation from start to finish

- Tailored performance: Choose a strain to match the wine’s style, structure, and flavor goals

- Lower risk of spoilage: Outcompetes unwanted wild microbes

Limitations:

- Less spontaneity: You sacrifice some of the unknown character and potential complexity of a native ferment

- Less expression of place: Commercial yeast may dominate the flavor profile instead of the vineyard

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Some winemakers swear by native fermentation for its authenticity. Others rely on cultured yeast for precision and peace of mind.

At Willowcroft, we recognize the value of both approaches. For certain small-batch or expressive wines, native fermentations can shine. For other wines—particularly those with delicate balance or specific style goals—cultured strains offer important control and consistency.

Ultimately, the best yeast is the one that lets the grape, the vintage, and the vineyard speak most clearly.

Yeast may be invisible, but its impact is undeniable. Whether wild or cultured, the tiny organisms doing the heavy lifting during fermentation help craft every swirl, sniff, and sip.

So next time you enjoy a Willowcroft wine, know that behind the scenes—at a cellular level—a carefully chosen yeast helped shape that wine’s unique story.

Wine Diamonds: Not a Flaw, But a Sign of Quality

What Those Crystals in Your Wine Bottle Really Mean

Ever poured a beautiful glass of wine and noticed a few shimmering crystals at the bottom, or maybe clinging to the cork? If your first instinct was concern, you’re not alone.

But don’t worry—those sparkly specks are known as tartrate crystals, or more affectionately: wine diamonds. They’re not only harmless, they’re a sign that your wine is authentic, natural, and minimally processed.

At Willowcroft, where we emphasize gentle winemaking and purity of expression, wine diamonds are simply part of the story. Let’s explore what they are, why they form, and why they’re worth celebrating, not avoiding.

Tartrate crystals are solid deposits that form when tartaric acid, one of the key natural acids in grapes, binds with potassium, another naturally occurring element in wine. These two components can join to form potassium bitartrate—the same compound you may know as cream of tartar in your baking cabinet.

Over time, especially in cooler temperatures, these crystals can settle at the bottom of the bottle or adhere to the cork.

Tartaric acid is temperature-sensitive. When wine—especially white wine—is chilled to very low temperatures (typically below 40°F / 4°C), it becomes less able to hold tartaric acid in solution. As a result, the acid precipitates out as crystals.

You’re more likely to see wine diamonds if:

- The wine has been stored in the fridge for an extended period

- The wine has not undergone cold stabilization, a common (but optional) winemaking step

- The wine is high in natural acidity, like many of the crisp, aromatic whites Willowcroft produces

Wine diamonds don’t affect the flavor, aroma, texture, or safety of the wine in any way. In fact, their presence can actually signal quality and integrity.

They’re natural – They’re made of grape components, not foreign substances.

They mean the wine is minimally processed – Wines that skip cold stabilization (a process where wine is chilled to force these crystals out before bottling) retain more of their natural acidity, freshness, and age-worthiness.

They signal gentle handling – The absence of over-filtration or additives shows that the winemaker chose to let the wine speak for itself.

First, smile—you’ve got the good stuff. But if the appearance of wine diamonds bothers you, here’s what you can do:

- On the cork? Just wipe them off with a napkin or cloth.

- In the bottle? Either:

- Decant the wine through a mesh strainer, cheesecloth, or coffee filter

- Let the crystals settle at the bottom and pour gently to avoid disturbing them

They’re completely safe to consume, but most people prefer to leave them in the bottle.

We believe that the best wines come from thoughtful farming and restrained winemaking. That means embracing the occasional natural element—like wine diamonds—as part of a wine’s story.

When you choose a Willowcroft white wine that hasn’t been cold stabilized, you’re tasting more than just fruit—you’re tasting the vineyard, the vintage, and the winemaker’s respect for nature.

Wine diamonds may look unusual, but they’re a sparkling sign of authenticity. In an industry filled with manipulation, they stand as a reminder that great wine isn’t always perfectly polished—it’s honest.

So the next time you find crystals in your bottle, don’t fret. Consider it a gem of a discovery.

Old Vines, Timeless Wines: What 40+ Years Means in the Vineyard

A Willowcroft Perspective on the Power of Age

A Willowcroft Perspective on the Power of Age

In wine, there’s something magical about the word “old.” Old cellars, old barrels, old vintages—and, of course, old vines. But what does “old vine” actually mean? Is there a specific age? A special certification? Or is it simply marketing?

At Willowcroft, many of our original vines—planted in 1981—are now over 40 years old, making them among the oldest in Virginia. These vines, with decades of seasons behind them, produce fruit that reflects both history and resilience.

Let’s explore what makes an old vine special—and how their quiet strength shows up in your glass.

Surprisingly, there’s no universal legal definition for "old vine." In most wine regions, it’s a subjective term. That said, here’s a general guide:

Vines 20-30 years old often start to qualify as "old" in terms of reduced yields and increased concentration.

Many producers and organizations see 50+ years as the gold standard for truly old vines.

At Willowcroft, our 40+ year-old vines sit comfortably in that distinguished middle, with maturity that shines through vintage after vintage.

As vines age, their growth slows. They produce smaller yields, but the fruit tends to have a greater concentration of flavor and aroma. These berries often pack more intense sugars, acids, and phenolic compounds, translating into wines with depth and complexity.

- 💧 Deep Roots:

Older vines develop extensive root systems, reaching deep into the soil to access water and nutrients younger vines can’t. This not only helps in dry conditions but also allows the grapes to draw from a broader palette of minerals, adding layers of terroir expression to the wine. - 🌞 Resilience:

With decades of adaptation, old vines can better handle environmental stresses—whether it’s a hot, humid Virginia summer or an unusually dry season. Their established systems make them naturally hardy. - 🪞 Terroir on Display:

Because they rely less on surface water and nutrients, old vines are more influenced by the deeper subsoil. This means their fruit often captures the true character of the vineyard’s terroir—soil, slope, and climate in harmonious balance.

While every vineyard and varietal is different, old vine wines are often described as:

- More concentrated in fruit flavor

- Silky in texture with fine, integrated tannins

- Complex, offering layered aromas and a longer finish

- Balanced, thanks to consistent, even ripening

At Willowcroft, you may notice these qualities in wines like our Chardonnay or Cabernet Franc, crafted from vines that have been growing since Ronald Reagan was president and MTV still played music videos.

When we planted our first vines in 1981, we couldn’t have known how their deep roots would shape not only our wines but also the history of Virginia winemaking. These vines, now over four decades old, are living proof that patience in the vineyard pays off in the glass.

Each harvest is a reflection of their long relationship with the land, through droughts, storms, and sunny seasons alike.

So next time you see “old vine” on a bottle—or sip a Willowcroft wine made from 40+ year-old fruit—pause for a moment. You’re tasting not just grapes but the echoes of years past: the summers, the storms, and the steady work of roots digging deep into Catoctin Ridge.

Visit us and experience wines crafted from some of Loudoun’s oldest vines. Every pour is a piece of Willowcroft’s 40+ year legacy.

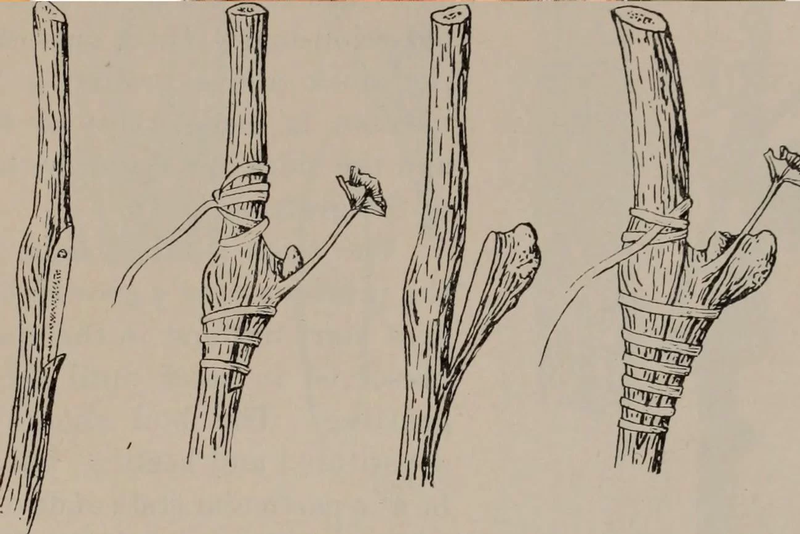

Rootstock Rebellion: How the Bottom Half of the Vine Shapes the Wine

The Unsung Hero Beneath Every Great Vintage

Ask a wine lover to name what shapes a wine’s character, and you’ll hear about grape varieties, climate, barrels—even yeast. But there’s one key player almost no one talks about: rootstocks.

These humble underground structures don’t make headlines or tasting notes, but they’re the very foundation of modern viticulture. They protect against pests, adapt vines to challenging soils, and influence everything from how grapes ripen to how the wine tastes. At Willowcroft, where we farm without irrigation and face Virginia’s humid summers, choosing the right rootstock isn’t optional—it’s vital.

So why don’t we hear more about them? To answer that, let’s dig into history, science, and a little Texas-sized adventure.

In simplest terms, a rootstock is the underground part of the vine—the roots—that’s grafted to the fruiting vine (the part above ground that produces the grapes). The fruiting vine is typically Vitis vinifera, the classic European grapevine species behind beloved varietals like Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot.

The rootstock, however, often comes from other grape species. Why? Because it acts like the engine of growth, protecting vines from pests, diseases, and environmental stress. It also influences vigor, water uptake, nutrient absorption, and even how a grapevine copes with Virginia’s frequent heat and humidity.

Rootstocks became essential during the 19th century when Europe’s vineyards were nearly wiped out by phylloxera, a tiny root-feeding insect native to North America. European vinifera vines had no resistance to the pest. The solution? Grafting them onto American rootstocks, which had evolved alongside phylloxera and developed natural defenses.

The first rootstocks tried—Vitis riparia—thrived in moist, fertile riverbank soils but failed in the dry, calcareous soils of regions like Champagne and Burgundy. Then came Vitis rupestris, better suited to stony soils but still unhappy in limestone-rich areas.

The breakthrough came when botanists like Pierre Viala and Thomas Volney Munson identified Vitis Berlandieri, a Texas native thriving in dry, chalky soils. Though difficult to propagate, Berlandieri became the backbone for hybrid rootstocks like 41B, which saved French vineyards and remains in use today.

Virginia’s climate brings its own set of hurdles for grapevines. Our summers often deliver long stretches of heat and humidity without relief, creating the perfect conditions for fungal diseases like powdery mildew and botrytis. Pair that with dry-farmed hillsides and variable soils, and rootstock selection becomes not just important, but essential.

The right rootstock helps balance vigor, resist disease, and manage water uptake in these demanding conditions. Some, like Petit Verdot’s small, tight clusters, naturally help resist moisture intrusion, but beneath the surface, it’s the rootstock doing much of the heavy lifting.

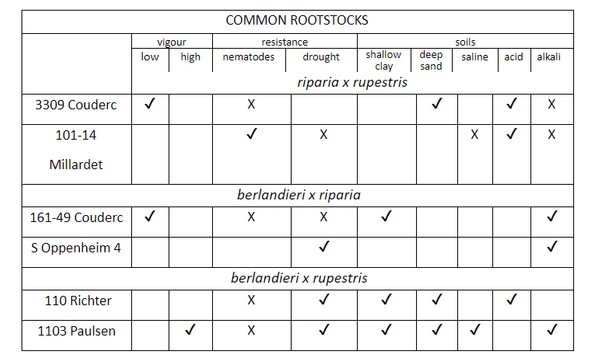

💡 To better understand how different rootstocks perform, here’s a quick chart showing key rootstock types, their strengths, and where they shine in the vineyard:

This snapshot helps demystify the role of rootstocks and shows why their selection matters as much as the grape variety grafted above them.

Today, nearly all commercial vineyards rely on rootstocks derived from the same small group of species: vinifera, riparia, rupestris, and Berlandieri. But nature doesn’t stand still. Phylloxera has evolved into numerous biotypes and superclones, while climate change introduces new challenges like extreme drought and shifting soil salinity.

Some researchers are exploring wild Asian grape species for new traits. Others argue for modern methods, including genetic modification (GM), to develop next-generation rootstocks. This remains controversial, but so was grafting American roots to French vines—until it saved the world’s wine industry.

Rootstocks are more than a technicality—they shape:

🌿 Vine vigor and health

💧 Drought tolerance and disease resistance

🍇 Ripening speed and fruit quality

🌱 Sustainability in challenging climates

At Willowcroft, we see them as quiet partners in the vineyard, helping us produce elegant, expressive wines—year after year—even in Virginia’s demanding environment.

So next time you swirl a glass of Petit Verdot or Chardonnay, raise a silent toast to the roots beneath your feet.

Visit Willowcroft for a tasting or tour, and ask us about the vines in your glass. There’s a world of science and history lying just below the soil.

🍇 Grape Clones & Hybrids: What They Are and Why They Matter

A Willowcroft Deep Dive into the Genetics of Great Wine

Not all Chardonnay is created equal.

Not even all Merlot.

In fact, even within the same vineyard block, the grapes growing just a few feet apart might come from entirely different genetic lineages.

Most wine lovers are surprised to learn how much grape genetics influence what’s in their glass. At Willowcroft, we take pride in our deep connection to both classic vinifera grapes—like Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay, which were among our original plantings—and to modern hybrid varieties that have helped us thrive in Virginia’s unique growing environment.

Understanding how clones and hybrids work is key to appreciating the science and artistry behind every bottle we produce. And no, none of this involves GMOs—so let’s set the record straight.

Clones are genetically identical copies of a single "mother vine" that showed exceptional traits, like superior flavor, disease resistance, or early ripening. Cuttings, not seeds, propagate these vines, allowing them to retain the exact DNA of their origin.

Think of clones as siblings from the same exceptional parent, each expressing slightly different characteristics based on where they’re planted. For example, Chardonnay Clone 96 may bring out bright citrus and body, while Clone 76 delivers more floral and elegant tones.

Across the industry, clonal selection is key to maximizing quality. It helps us:

- Adapt to different vineyard blocks

- Improve disease resistance naturally

- Fine-tune flavor and ripening windows for our dry-farmed, hillside sites

From the beginning, Willowcroft has championed vinifera—the noble European species behind the world’s most iconic wines. Our early plantings of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chardonnay were rooted in this tradition and remain foundational to our portfolio today.

But Virginia is not Bordeaux or Burgundy. Our summers bring persistent heat and humidity, often without a reprieve from the heat. These humid streaks—lasting days, weeks, or even months—can place significant stress on the vines, increasing the risk of fungal diseases, rot, and uneven ripening. That’s where clonal selection and strategic hybrid use become critical. By selecting varietals and clones adapted to our specific conditions—such as Petit Verdot, whose small, tight clusters naturally help resist moisture intrusion—we can produce wines of integrity, character, and resilience, even in challenging years.

Hybrid grapes are crosses between different grape species, typically blending vinifera with native American grapes like Vitis labrusca or Vitis riparia. These intentional crosses are bred for strength: they’re often more resistant to disease, cold, humidity, and pests.

At Willowcroft, we proudly grow several hybrids that have earned fan-favorite status:

- Seyval Blanc – Crisp and citrusy, great for warm days and cool nights

- Chambourcin – Deep, fruit-forward, and perfect with pork or lamb

- Traminette – Spicy and floral, with Gewürztraminer in its lineage

Here’s the truth:

Hybrids are not genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Hybrids are created through traditional plant breeding—crossing two grape varieties and selecting the best offspring. It’s a slow, deliberate process, often taking years or even decades.

GMOs, on the other hand, involve lab-based DNA manipulation, often introducing genes from unrelated species. Currently, no GMO grapes are used in commercial winemaking in the United States.

So while some folks hear “hybrid” and think “science experiment,” the reality is that hybrids are a time-honored, nature-guided solution to challenges like climate, pests, and sustainability.

Your wine starts long before the bottle—with decisions about what to plant, where, and why. Whether we’re choosing a Cab Franc clone for improved ripening or a hybrid like Seyval to reduce disease pressure, every choice in the vineyard shapes what you taste in the glass.

These selections affect:

- 🍇 Flavor profiles and aromatic intensity

- 🌿 Farming sustainability (especially in dry-farmed systems like ours)

- 🌦️ Adaptation to climate and disease pressure

- 📦 Consistency across vintages and vineyard blocks

Join us in the tasting room or attend one of our vineyard tours to see how these choices play out in real time, from bud break to bottle. The more you know, the better it tastes—and we’re always happy to pour and chat.

🥂 Wine for Breakfast (Sort Of): Perfect Brunch Pairings for Each Varietal

A Willowcroft Guide to Sipping Through Summer Brunch

A Willowcroft Guide to Sipping Through Summer Brunch

We’re not saying you should pour a glass of Cabernet with your cereal—but when it comes to summer brunch, wine absolutely belongs at the table. Think of it as elevating your leisurely late morning meal with fresh flavors and the perfect Virginia pour.

Whether you’re hosting a weekend brunch on the porch or bringing a bottle to a potluck-style picnic, Willowcroft wines pair beautifully with everything from savory scrambles to fruity pastries. Here’s your guide to mixing, matching, and sipping like a pro—all before noon.

Creamy eggs, salty ham, and melted cheese deserve a wine that can match richness with elegance. Willowcroft’s Chardonnay Reserve brings just enough body and oak to stand up to the dish, while its smooth finish complements without overpowering.

- Why it works: Balanced acidity, subtle vanilla, and a creamy texture mirror the mouthfeel of a classic quiche.

- Serve it with:

- Spinach and mushroom quiche

- Bacon & Swiss egg bites

- Buttery croissants with brie

This Mediterranean-inspired dish is bursting with brightness, and that calls for an equally zesty pairing. Seyval Blanc, with its crisp citrus and herbal notes, plays beautifully with tangy feta and the umami of sun-dried tomato.

- Why it works: The acidity in the wine cuts through the richness of the eggs and highlights savory herbs.

- Serve it with:

- Toasted sourdough

- Herb-roasted potatoes

- Grilled asparagus or summer squash

Crispy, juicy fried chicken and fluffy biscuits are the epitome of picnic brunch perfection. Pair them with Vidal Blanc, a lightly sweet, fruit-forward white that brings freshness to a rich, crunchy plate.

- Why it works: Vidal’s hint of sweetness contrasts with salty, fried flavors, especially with a drizzle of honey or hot sauce.

- Serve it with:

- Peach preserves or honey butter

- Summer slaw

- Cornbread muffins

Nothing says summer brunch like ripe berries—and Rose of Sharon, Willowcroft’s off-dry rosé, is the match made in seasonal heaven. With notes of strawberry, cherry, and a delicate floral finish, it enhances berry flavors in every bite.

- Why it works: Fruit meets fruit. The slight sweetness of the wine mirrors the natural sugars in berries.

- Serve it with:

- Berry-stuffed crepes

- Lemon-blueberry muffins

- Strawberry shortcake parfaits

Forget the store-bought bubbly—elevate your mimosa game with Sauvage Blanc de Blanc, Willowcroft’s dry, elegant sparkling wine. Its crisp citrus notes and fine bubbles make it the perfect base for a fresh summer mimosa—or enjoy it straight for a bright brunch sip.

- Fun idea:

- Create a DIY mimosa bar with fresh juices and fresh berries or fruit, and let guests mix their own!

- Also pairs well with:

- Smoked salmon bagels

- Melon & prosciutto

- Deviled eggs with herbs

At Willowcroft, we believe great wine belongs at every table—including the brunch table. Whether you're dining al fresco or picnicking in the backyard, these pairings make summer mornings feel just a little more special.

So go ahead—sip before noon. We won’t tell.

Visit our tasting room to stock up, or order your wines online and have them shipped in time for your next weekend gathering. Cheers to brunch, Virginia-style!

Unexpected Pairings: Virginia Wines & Global Takeout

A Willowcroft Guide to Sipping Local with International Flavor

A Willowcroft Guide to Sipping Local with International Flavor

In the greater Washington D.C. area, our takeout menus read like a passport—offering everything from spicy Thai noodles to soulful Creole classics, tacos that transport us to Mexico City, and pasta that could pass for a Roman holiday. But with so many vibrant flavors, how do you choose the right wine?

Here’s a twist: you don’t need to reach for an imported bottle. Willowcroft Farm Vineyards produces Virginia-grown wines that pair beautifully with global cuisines, right from our perch atop the Catoctin Ridge.

Whether you're winding down after work or hosting a casual dinner, here are some fresh and unexpected pairings to try with your favorite takeout.

Think: Thai, Indian, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese

Go-To Wines: Albariño, Traminette, Chambourcin, Riesling

Why it works: From the heat of Thai curries to the umami of Korean BBQ, Asian dishes pack layers of spice, aromatics, and sweet-savory balance. Willowcroft’s aromatic whites and juicy reds are built to complement—not compete—with these flavors.

Try pairing:

- Albariño with Thai green curry or Vietnamese lemongrass chicken

- Traminette with pork dumplings or General Tso’s chicken

- Chambourcin slightly chilled with chicken tikka masala or lamb vindaloo

- Dry Riesling with sushi, pad Thai, or pho

Think: Pasta, Pizza, Eggplant Parm, Meatballs

Go-To Wines: Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Seyval Blanc, Chardonnay Reserve

Why it works: Italian dishes tend to be rich, savory, and comforting. Red sauces, herbs, and cheese pair well with structured reds, while creamy pastas or seafood dishes complement full-bodied whites.

Try pairing:

- Merlot with meat lasagna or eggplant parm

- Cabernet Franc with wood-fired pizza or sausage bolognese

- Seyval Blanc with chicken piccata or pesto pasta

- Chardonnay Reserve with fettuccine Alfredo or shrimp scampi

Think: Tacos, Enchiladas, Empanadas, Cuban Sandwiches

Go-To Wines: Sauvage Rosé, Riesling, Chambourcin, Vidal Blanc

Why it works: Spice, citrus, and smoky meats meet their match in vibrant, fruit-forward wines that can cool heat and highlight bold flavors.

Try pairing:

- Sauvage Rosé with carnitas tacos or shrimp ceviche

- Riesling with chicken enchiladas verde or tamales

- Chambourcin with beef empanadas or Cuban sandwiches

- Vidal Blanc with grilled corn elote or arroz con pollo

🫒 Spanish Tapas & Mediterranean Bites

- Think: Patatas Bravas, Jamón, Olives, Paella

- Go-To Wines: Albariño, Petit Verdot, Chardonnay, Applause

- Why it works: Tapas are made for grazing—and so are wines that can handle a range of salty, savory, and herby flavors. You want wines that stay interesting across the whole table.

Try pairing:

- Albariño with seafood paella or garlic shrimp

- Petit Verdot with grilled chorizo or lamb skewers

- Applause with Manchego and Marcona almonds

- Chardonnay with roasted peppers or tortilla Española

Think: Jerk Chicken, Gumbo, Fried Plantains, Crab Cakes

Go-To Wines: Traminette, Petit Verdot, Vidal Blanc, Rosé of Sharon

Why it works: These dishes bring spice, sweetness, and smoke. You need wines with bold flavor and balance—aromatic whites and deep reds shine here.

Try pairing:

- Traminette with jerk chicken or fried plantains

- Petit Verdot with gumbo or blackened fish

- Vidal Blanc with coconut curry shrimp or mango salsa

- Rosé of Sharon with crab cakes or spicy sausage jambalaya

Great wine doesn’t have to come from the same country as your food. It just has to bring balance, brightness, and joy to the table. At Willowcroft, we believe your local bottle should pair just as effortlessly with pad Thai or tacos as it does with pork chops and Virginia cheeses.

So the next time you grab takeout, skip the beer or soda, and reach for a glass of Virginia-grown wine. Your palate will thank you.

📸 Share Your Takeout + Wine Night!

Tag @WillowcroftWine on Instagram or Facebook and show us how you're pairing Willowcroft with global flavors.

Rooted in Resilience: The First Grapes at Willowcroft and Their Legacy Today

When Lew Parker first planted grapes at Willowcroft Farm Vineyards in 1980, there was no roadmap—only a dream, a hillside, and the hope that Virginia could one day rival the great wine regions of Europe. At the time, the very idea of growing European grape varieties, known as Vitis vinifera, was considered risky, even reckless, by local advisors from the Virginia Extension Service. But like many pioneers, Lew believed that the best way to grow was to take a chance.

The first vines planted, Cabernet Sauvignon, Riesling, Chardonnay, and Seyval, didn’t make it. A harsh introduction to the challenges of Virginia viticulture resulted in the entire initial planting failing. But that didn’t stop Lew. He replanted in 1981, and this second planting survived. Many of those vines continue to thrive today in our home vineyard, their deep roots telling the story of Willowcroft’s perseverance and vision.

Each variety chosen in those early days represented a bold step toward redefining what Virginia wine could be:

- Cabernet Sauvignon, a bold red grape from Bordeaux, was selected for its potential to bring structure and aging ability to Virginia reds.

- Riesling, a grape native to Germany’s cooler climates, offered aromatic white wine potential and acidity that could balance Virginia’s warmth.

- Chardonnay, the queen of white grapes, was a natural choice for producing elegant, versatile wines.

- Seyval, a French-American hybrid, provided insurance—hardier and more disease-resistant, Seyval could deliver reliable harvests when other vines struggled.

At the time, little was known about how to cultivate these varieties successfully in the unique microclimates of Virginia. It was all trial and error. The soil, slope, canopy management, and disease pressure were all things that had to be learned the hard way. But these early choices laid the foundation for what would become one of the most exciting wine regions in the country.

The decision to plant Vitis vinifera was a revolutionary one. Native American grapes and early hybrids had been cultivated in Virginia for centuries, but their wines were often considered musky, overly sweet, or lacking finesse. European settlers longed for the wines of home, and Vitis vinifera was the key.

Today, these European varieties make up more than 75% of Virginia’s grape production by tonnage. They have transformed the state’s reputation from a fledgling curiosity into a nationally recognized wine region with over 300 wineries. At Willowcroft, we continue to honor that legacy by producing high-quality vinifera wines—Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Chardonnay, Albarino, and yes, still our original Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling.

What makes those original plantings remarkable is not just their age—it’s their continued relevance. Despite decades of experimentation across the state, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and Riesling remain cornerstones of Virginia’s premium wine scene. These grapes have proven adaptable, expressive of Virginia’s terroir, and capable of producing wines with elegance, balance, and depth.

As for Seyval, it remains a staple at Willowcroft—a reminder that hybrid varieties have an essential place in our portfolio, offering resilience and versatility, especially as climate unpredictability increases.

Walking through the home vineyard today, you can still see those early vines—knotted, gnarled, and wise. They’ve weathered frost and sun, drought and deluge. And they still bear fruit that tells a story: of vision, of patience, and of a belief in Virginia’s potential before the rest of the world was ready to believe with us.

Willowcroft is proud to be the oldest winery in Loudoun County, a cornerstone of Virginia wine’s modern era. As we continue to innovate and expand our offerings, we never forget the vines that started it all—those planted not just in soil, but in hope.

Perfectly Imperfect: How to Embrace Faults and Find Your Favorite Wine

In the world of wine, perfection is elusive, which is precisely what makes it so captivating.

In the world of wine, perfection is elusive, which is precisely what makes it so captivating.

Much like people, every bottle of wine carries its own story, quirks, and character. Sometimes that story is rich and complex; other times, it’s a little offbeat. You may have heard terms like corked, oxidized, or reductive thrown around in tasting rooms or wine forums—but what do these so-called “faults” really mean, and should they scare you off?

Let’s uncork the truth.

A wine fault is typically defined as a chemical or microbial issue that deviates from what’s considered a “sound” wine. These can result from problems during winemaking, bottling, storage, or even cork taint. But here’s the catch: not all deviations are dealbreakers. In fact, some are simply nuances, and whether or not they bother you depends entirely on your palate.

Just like some people love blue cheese while others can’t stand it, wine “flaws” are often subjective. That little funky note or oxidative edge? It might just be what sets a wine apart in a way that makes you fall in love.

- Cork Taint (TCA): This one is pretty universally disliked—described as musty, moldy, or like wet cardboard. It mutes fruit flavors and makes the wine seem flat. If you encounter it, don’t feel bad about sending the bottle back or asking for a replacement.

- Oxidation: When a wine has been overly exposed to oxygen, it can taste like bruised apples or lose its vibrancy. But in some styles—think Sherry or older whites—oxidative notes are a feature, not a bug.

- Volatile Acidity (VA): A whiff of vinegar or nail polish remover can indicate high VA. While excessive VA can be jarring, a touch can actually enhance a wine’s complexity and brightness, especially in reds.

- Brettanomyces (“Brett”): This wild yeast brings earthy, leathery, or barnyard aromas. To some, it's rustic charm; to others, a flaw. Like spice in a dish, a little might be delicious—but too much can overpower.

- Reduction: The opposite of oxidation, reduction can smell like struck matches or rubber. Swirl your glass—often, those notes will dissipate, revealing layered, savory elements underneath.

Mouse is one of the more polarizing and, frankly, bizarre faults in wine. It's not something you smell—it’s something you feel after the sip, when the finish leaves your mouth tasting oddly like a hamster cage. Yes, really.

People describe it in creative (and colorful) ways: urine-soaked sawdust, old cured meats, or even “my teenage dog’s breath.” It’s most common in natural wines made without added sulfites and tends to emerge after the bottle has been open for a while, so a wine that seems fine at first might develop that off-putting flavor 30 minutes in.

Mouse is tricky because it’s not always present, and it’s not always immediately apparent. If you notice it, it’s usually best to move on to another wine, it's one of those faults that doesn’t fade away with food or time. Still, it’s a good reminder that even the most lovingly made wines can have quirks.

At Willowcroft, wine shouldn’t be intimidating—it should be an experience. Not every bottle will be perfect, but it might be perfect for you. And that’s what makes wine tasting so fun: every vintage, every varietal, every sip is an invitation to discover something new.

Whether you’re sipping a crisp Seyval on the porch or diving into a bold Bordeaux blend by the fire, remember: wine is meant to be enjoyed, not analyzed to death.

Next time something tastes a little different, don’t rush to judgment. Give it a swirl, give it a chance—and if it’s not for you, that’s okay too. There’s a world of wine waiting, full of character, depth, and maybe even a few charming flaws.

Like people, wine is rarely perfect, but it might be the perfect match for you.